Informing the President; speaking truth to power; being the nation’s “first line of defense.” These mottos form the core ethos of the US intelligence community (IC), a network of 18 agencies, departments, and military services across the executive branch charged with collecting, analyzing, and delivering foreign intelligence to senior US leaders so they can make critical decisions about national security.

The community plays a crucial role in informing US government policy and safeguarding national security, including in areas related to emerging technologies. The IC employs tens of thousands of analysts, technical specialists, and support staff—offering valuable career opportunities for those interested in the intersection of technology and national security.

IC work offers valuable opportunities to advance your career in national security and inform the policymaking process by providing objective information. But if you’re aiming to contribute more directly to policy decisions or promote particular policies, consider instead working in Congress, think tanks, or federal agencies outside of the IC.

Background on “the IC”

What does the IC do?

Nearly every nation has an intelligence agency charged with helping national leaders understand and anticipate threats and opportunities, whether from terrorist attacks, cyber operations, or infectious diseases. In broader terms, many individuals and organizations seek to inform policymakers on foreign policy issues both big and small, including academics, think tanks, and public interest advocacy groups. But what sets the IC apart is its focus on gathering and assessing secret information for decision advantage.

Put plainly, the IC’s job is to think about the full range of national threats, both near-term and far into the future, and help decision-makers understand and counter those threats. The US IC employs tens of thousands of civil servants who range in focus and background, from analysts, engineers, computer scientists, staff support personnel, and accountants—you name it, and the IC probably has it. STEM, humanities, social science, and language-focused graduates will all find a role at one of the 18 IC entities, typically joining via the excepted or competitive civil service depending on the agency and role.

The key characteristics of IC work include:

- Objectivity: Intelligence aims to be non-partisan and non-policy prescriptive, focusing on information collection and analysis rather than recommendations.

- Multidisciplinary approach: The IC draws on diverse expertise to provide comprehensive analyses.

- Security-focused environment: Work often involves classified information and strict security protocols.

- Customer-centric: Intelligence serves specific “customers”—decision-makers who receive the final analytical products.

The IC’s diverse types of roles and activities

The IC’s work spans many topics from traditional geopolitical analysis to technical countermeasure design for emerging threats in AI, biotech, cyberspace, and other advanced technologies. This breadth allows professionals with various backgrounds, including those in tech fields, to contribute meaningfully to national security.

The focus areas of IC analysts are typically organized into so-called “accounts,” referring to a specific topic, issue, or area of responsibility assigned to an analyst or team of analysts. These accounts are usually clustered into two main categories (“functional” and “regional”).

Functional and regional analysts

Functional analysts focus on transnational issues or threats that span geographic boundaries, such as:

- Counterterrorism (CT): Analyzing terrorist groups, their capabilities, leaders, and overall threat activities.

- Counterproliferation (CP): Monitoring the attempted spread of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) technologies and capabilities by state and non-state actors.

- Cyber: Assessing cyber threats and vulnerabilities in digital infrastructure.

- Economic: Analyzing global economic trends, economic statecraft issues (e.g. tarifs, export controls, supply chain vulnerabilities), financial markets, and the impact on political stability.

- Political: Analyzing foreign political leaders, the foreign policies of other countries, and global political dynamics, including governance issues, ideological movements, and political risks affecting stability and international alliances.

- Science, technology, and weapons (STW): Evaluating technologies, advanced conventional weapons systems, and related emerging capabilities and their national security implications, including AI and biotechnology.

Regional analysts specialize in specific geographic areas, providing in-depth knowledge of the political, economic, and social dynamics of particular countries or regions. Key regional focuses include:

- East Asia and Pacific

- Europe and Eurasia

- Middle East and North Africa

- South and Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- Western Hemisphere

Technical roles

For professionals with technical backgrounds, the IC offers many opportunities to leverage their skills from analytical to applied/operational roles:

- Technical Intelligence Analysis: Applying domain expertise to assess foreign technological capabilities, such as evaluating adversaries’ AI systems or quantum computing advancements.

- Research & Development: Creating cutting-edge tools and technologies for intelligence collection and analysis, like developing machine learning algorithms for processing satellite imagery or designing secure communication systems.

- Cyber Operations: Defending against and conducting cyber intelligence activities, including penetration testing, malware analysis, network defense, and offensive cyber operations.

- Data Science and Analytics: Developing and applying advanced data analysis techniques to extract insights from large datasets.

- Signals Intelligence (SIGINT): Intercepting and analyzing electronic communications and signals.

- Geospatial Intelligence (GEOINT): Analyzing and interpreting satellite imagery and geospatial data.

Intelligence collectors and case officers

Popular media often romanticizes the work of intelligence collectors and case officers, yet the reality is more complex and nuanced than typically portrayed in movies:

- Human Intelligence (HUMINT) Collectors: These professionals, often called “case officers”, cultivate and manage human sources to gather intelligence. Their work involves building relationships, assessing source credibility, and securely transmitting information. Unlike movie depictions, this rarely involves high-speed chases or shootouts, but rather requires patience, interpersonal skills, and meticulous attention to detail.

- Technical Collectors: These specialists operate sophisticated collection systems, such as signals intelligence equipment or satellite systems. Their work often involves maintaining and optimizing complex technical infrastructure rather than engaging in covert operations.

- Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) Collectors: These professionals gather and analyze publicly available information from sources like social media, news outlets, and academic publications. While less glamorous than fictional portrayals, OSINT is increasingly crucial in the digital age.

- Counterintelligence Officers: These specialists work to detect, deter, and neutralize foreign intelligence activities against the US. Their work often involves careful investigation and analysis rather than dramatic confrontations.

- Staff Operations Officers: These professionals plan and execute intelligence operations, which can range from coordinating collection efforts to managing covert action programs, a unique purview by law of CIA. While some aspects of their work may involve fieldcraft, much of it centers on careful planning, risk assessment, and coordination with other IC elements.

In reality, the work of collectors and operational staff is often methodical, detail-oriented, and focused on long-term relationship building and information gathering. It requires strong analytical skills, cultural sensitivity, and the ability to work within complex legal and ethical frameworks.

Why might you (not) want to work in the IC?

The IC offers unique opportunities for those interested in national security and emerging technologies to make a difference and advance their career. IC analysts and technical specialists are equipped to work on many different areas, such as cyber operations, space capabilities, WMD mitigation, wargaming, and future assessments. IC work also allows you to translate complex technical issues—like those in AI and quantum computing—into insights and warnings for senior policymakers.

Upsides to IC work

Here are some reasons to consider an IC career:

- Mission focus and opportunity for impact: Your work directly informs critical national security decisions and policies. You’ll have opportunities to contribute to high-level briefings, inform policy, and craft strategic assessments that shape US foreign policy and national security strategies. Your analysis could influence decisions on issues ranging from counterterrorism operations to nuclear nonproliferation efforts.

- Career development: The IC supports continuous learning, including through advanced degrees and specialized training. For example, some agencies have programs to sponsor employees’ graduate work, including full-time master’s programs at top universities in exchange for a commitment to continued service for a specified period. These programs can cover various fields relevant to national security, from data science and cybersecurity to area studies and foreign languages. There are also many other professional development opportunities, including policy rotations—like temporary assignments to policymaking bodies like the National Security Council—and research stints at government laboratories, prominent think tanks, and universities. This allows employees to broaden their expertise, expand their networks, and bring fresh perspectives back to their agencies.

- Security Clearance: IC work allows (and requires) you to gain a security clearance, which allows access to sensitive information and can be valuable for future career opportunities. While clearances don’t always transfer easily between agencies, having one can potentially streamline the process for future national security jobs, either in government or government-facing industries.

- Access to some cutting-edge capabilities: Although government acquisition processes for cutting edge technologies lag behind private industry at times, working in the IC can offer unique opportunities to engage with advanced platforms, specialized capabilities, and bespoke technologies dedicated to collection and analysis missions.

- Job security: The IC offers generally stable employment with competitive benefits. Government positions typically provide strong job security, and the specialized nature of intelligence work often leads to long-term career stability. Benefits usually include health insurance, retirement plans, paid time off, and sometimes unique perks like hazard pay for certain assignments or student loan repayment programs.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration: IC work often involves collaborating with experts from diverse fields on complex, multifaceted challenges. You might find yourself working with data scientists, linguists, regional specialists, military strategists, and technology experts all in a single day. This interdisciplinary environment fosters creative problem-solving and provides opportunities to expand your knowledge across various domains.

- Onward employment: Experience and skills gained in the IC, coupled with security clearances, often open doors to other impactful government positions or lucrative opportunities in the private sector, particularly in defense contracting, cybersecurity, and technology firms, where former IC professionals can leverage their unique expertise and networks.

- Policy rotations as career assignments for IC employees: Agencies will often temporarily assign—or “detail”—employees to work in different parts of the government. For IC employees, this can include temporary assignments serving as policymakers themselves. Policy rotations offer IC employees valuable opportunities, and typically last 12 to 24 months at locations such as the National Security Council staff, Department of State offices, or DOD policy offices. During these rotations, IC employees may serve as action officers and subject matter experts, draft policy memos, coordinate interagency efforts, and brief policymakers on intelligence matters. These assignments provide insights into how intelligence informs policy decisions, help develop networks across the policy community, and are often considered valuable for career advancement in the IC. Eligibility usually requires several years of IC experience, with each agency normally holding competitive internal applications to nominate 1 to 2 employees for final selection by the gaining department. The application process varies by agency but often involves internal applications, supervisor recommendations, and interviews with the host office.

Downsides to IC work

IC work also comes with several important potential negative aspects:

- Policy neutrality and limited policymaking roles: IC employees are bound by law to remain politically neutral and are also expected to remain neutral on policy matters. Analysts, for example, focus on providing objective assessments rather than advocating for specific policies, and this can be frustrating for those more interested in actively shaping policy. While the IC informs policymakers, it doesn’t make policy decisions itself.

- Secrecy: Much of your work will be classified, limiting your ability to discuss it with others or publish openly. You may not be able to list your specific employer or job title on professional networking sites like LinkedIn, and there may be other restrictions on personal blogging, social media use, and writing for public outlets. Even with close family and friends, including partners, you may be unable to discuss the details of your work.

- Ethical considerations: Intelligence work is inherently complex and sometimes faces ethical dilemmas related to national security decisions, which can be difficult to navigate. IC work requires accepting that safeguarding US interests is the primary objective, which can at times conflict with broader global interests.

- Bureaucracy: Like other large government organizations, IC agencies can move slowly and be resistant to change, sometimes clashing with an otherwise strong culture of decentralized interaction and questioning assumptions.

- Location constraints: Many IC jobs require working in specific locations, often in the Washington, DC, area, and can be inflexible on relocation options (but there are also some opportunities nationwide and overseas).

- Lack of work from home flexibility: Unlike an increasing number of high-skilled research jobs, IC work mostly cannot be done in a hybrid fashion, from home, or in unsecured spaces; as such, you will likely have to work from a “sensitive compartmented information facility” (SCIF), in which you’re unable to bring personal electronics of any kind. This can create a more rigid work environment and may impact work-life balance if you have competing personal obligations requiring flexibility. This can vary depending on your role and the amount of unclassified work involved, and some IC roles may allow for a degree of remote work (i.e. recruiting and industry engagement roles).

- Lengthy hiring process and limited privacy: Security clearance procedures can make the hiring process long and invasive. Most IC jobs require a polygraph examination, covering issues including criminal activity or illegal drug use; ties to foreign governments; falsifying security forms; involvement in espionage, sabotage, terrorist activities; and compromising classified information. Even after you get hired, IC work continuously requires a much higher level of personal disclosure than most other careers. You may be expected to share extensive personal information as part of background checks and ongoing security requirements.

IC members

The US IC consists of 18 organizations working together to conduct intelligence activities crucial for national security, though each agency has a specialized focus, culture, and hiring process. In the IC, ODNI and CIA are the only two independent agencies, with ODNI reporting directly to the President, while other IC entities fall under a specific cabinet department.

A significant portion of the IC operates under the Department of Defense (DOD), including several major agencies and the intelligence elements of the military services. The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), National Security Agency (NSA), National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), and National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) are all DOD components, each with its own specialized focus in defense intelligence. These agencies focus on strategic military intelligence issues, while branch-specific intelligence elements focus on operational and tactical intelligence collection and analysis.

Additionally, each branch of the military—Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and the newly established Space Force—maintains its own intelligence element, also under the DOD umbrella. These agencies often work closely with military operations and may have both civilian and military personnel. Their intelligence focus tends to be more directly tied to defense and military matters—known as “support to the warfighter” in addition to “support to the policymaker”—although they still contribute to the broader national security picture.

| Agency (hiring pages linked) | Primary focus | Career types | Emerging tech offices (examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) (independent) | Oversees & coordinates the entire IC | IC-relevant policy, Analysis, S&T, Mission Management | Economic Security & Emerging Technologies NIO for Emerging & Disruptive Technologies National Counterproliferation & Biosecurity Center |

| Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (independent) | Foreign intelligence & covert operations | Analysis, Operations, S&T, Support | Transnational & Technology Mission Center Directorate of Digital Innovation Directorate of Science & Technology Directorate of Analysis |

| National Security Agency (NSA) (part of DOD) | Signals intelligence & cybersecurity | Cybersecurity, Signals Intelligence, Research, Language Analysis | AI Security Center Cybersecurity Collaboration Center |

| Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) (part of DOD) | Military intelligence | Analysis, Human Intelligence, Technical Collection, Operations | Technology & Long-range Analysis Office |

| National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) (part of DOD) | Geospatial intelligence | Imagery Analysis, Cartography, Data Science, Engineering | Cybersecurity Operations Cell CP Division |

| National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) (part of DOD) | Developing, acquiring, launching, & managing satellite intelligence operations | Aerospace Engineering, Systems Engineering, Data Science | Mission Operations Directorate |

| Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) – Intelligence Branch (part of DOJ) | Domestic intelligence & counterintel | Special Agent, Intelligence Analyst, Language Specialist, STEM | Cyber Division |

| State Dep – Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) | Diplomatic intelligence | Foreign Affairs, Intelligence Analysis, Research | Technology & Innovation Office Office of Cyber Affairs |

| DHS – Office of Intelligence and Analysis | Homeland security intelligence | Intelligence Analysis, Cybersec., Law Enforcement | Cyber Intelligence Center |

| DOE – Office of Intelligence & Counterintel. | Energy, nuclear, & scientific intelligence | Scientific Intelligence, Counterintel | Intelligence Analysis Directorate Cyber Directorate |

| Dep. of the Treasury – Office of Intelligence & Analysis | Financial intelligence | Financial Analysis, Economic Analysis, Intelligence Analysis | Research & Analysis Division FinCEN |

| Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) – Intelligence Division | Drug-related intelligence | Intelligence Research, Special Agent, Diversion Investigator | Office of Investigative Technology |

| Army Intelligence (INSCOM) | Military intelligence for land operations | Intelligence Analysis, Signals Intelligence, Human Intelligence | Various national & special mission units |

| Naval Intelligence (ONI) | Maritime & naval intelligence | Intelligence Specialist, Cryptologic Technician, Special Warfare | Various national & special mission units |

| Air Force Intelligence | Aerospace & cyber intelligence | Intelligence Analyst, Special Investigations, Cyber Operations | Various national & special mission units |

| Marine Corps Intelligence (MCIA) | Expeditionary intelligence (e.g. supporting amphibious operations) | Intelligence Specialist, Counterintel, Signals Intelligence | Various national & special mission units |

| Coast Guard Intelligence (CGI) | Maritime domain awareness | Intelligence Specialist, Investigative Service | Various national & special mission units |

| Space Force Intelligence | Space domain awareness | Space Operations, Intelligence Analyst, Cyber Operations | Various national & special mission units |

The “federation” and its components

The IC is a federation of 18 separate organizations working together to conduct intelligence activities necessary for national security. The Director of National Intelligence (DNI) serves as the IC’s head and is the principal advisor to the President, National Security Council, and Homeland Security Council for intelligence matters. The DNI is the IC’s statutory leader, and was established by the 2004 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act to better integrate, deconflict, and bolster information sharing and collaboration across the IC after 9/11.

The DNI’s primary responsibilities encompass integrating the IC’s intelligence collection and analysis efforts, overseeing and directing the implementation of the National Intelligence Program (NIP) and developing the National Intelligence Strategy (NIS), and establishing objectives and priorities for collection, analysis, production, and dissemination of national intelligence. This centralized leadership aims to foster collaboration and efficiency across the various IC agencies.

But in practice interagency cooperation in the IC can be complex and sometimes challenging. While some post-9/11 reforms have improved information sharing, obstacles remain due to factors like classification levels, need-to-know restrictions, and differing organizational priorities and equities. The overlapping responsibilities of some agencies can lead to both cooperation and competition, and each agency’s unique culture and traditions can sometimes hinder collaboration.

Intelligence outside of the IC

Intelligence work and analysis extend beyond government agencies, with several entities contributing significantly to the intelligence landscape. This spans specific large companies, private firms focused on geopolitical risk analysis, social media companies conducting cyber threat actor detection, analysis, and takedown operations, and AI companies collecting information on potential malign uses of commercial AI models.

Organizations involved in intelligence work outside the IC

- Non-governmental organizations (NGOs): Organizations like Bellingcat use open-source intelligence (OSINT) techniques to investigate and report on global events, often complementing and sometimes preceding official intelligence assessments.

- Private sector companies: Many corporations, especially in the tech, finance, and defense sectors, have their own intelligence units focusing on threat intelligence for cybersecurity, geopolitical risk assessment for business operations, and market intelligence for strategic decision-making.

- Social media companies: Various social media platforms conduct extensive cyber threat actor detection, analysis, and takedown operations. These companies have developed sophisticated systems to identify and counter disinformation campaigns, cyber attacks, and other malicious activities on their platforms. Their vast user bases provide them with unique insights into emerging threats and global trends, which can be valuable for national security considerations.

- AI companies: Frontier AI companies are increasingly involved in intelligence-related activities, particularly in collecting and analyzing information on potential malign uses of commercial AI models. As AI technology advances, these companies are at the forefront of identifying and mitigating risks associated with AI misuse.

- Critical infrastructure: Utilities and companies, like those in energy, telecommunications, transportation, and financial services sectors, play a crucial role in intelligence gathering and analysis for threats to their enterprises. These companies operate vast networks and systems that are prime targets for cyber attacks and other security threats and, as a result, have developed sophisticated threat intelligence capabilities to protect their assets and operations. They often collaborate with government agencies to share information about emerging threats and vulnerabilities.

How the IC plugs into the policymaking process

Like any good business, intelligence agencies focus on serving “the customer,” a shorthand reference to policymakers who receive the final analytical “product” based on collected foreign intelligence on a given topic.

Crucially, while the IC informs policy, it does NOT make or directly implement policy. The IC’s role is to provide objective information and assessment so that policymakers can design policy on solid, factual grounding, not to advocate for specific policy outcomes. This separation is critical so that the IC maintains the integrity and credibility of the intelligence process.

For the US, the policy cycle is key for intelligence agencies to plug into the rhythm of decision-making. This process typically involves:

- Interagency Policy Committees (IPCs): These are lower-level working groups formed by representatives from agencies relevant to national security and foreign policy to discuss specific policy issues. They’re often the first point of contact for intelligence input into the policy process. Intelligence analysts may brief IPC members on relevant topics or provide written products to inform discussions.

- Deputies Committees (DCs): These are mid-level meetings of deputy heads of relevant agencies. At this level, intelligence agencies might provide more synthesized assessments or highlight particularly critical issues that have bubbled up from the IPC level.

- Principals Committees (PCs): These are high-level meetings of agency heads (“principals”) to make recommendations to the President. Here, intelligence inputs are typically distilled into key judgments and high-level assessments to inform strategic decision-making.

- National Security Council (NSC) meetings: At the highest level, these meetings are attended by the President, who chairs the council, along with statutory members including the Vice President, Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense, and Secretary of Energy. Other regular attendees often include the National Security Advisor, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Director of National Intelligence. Depending on the specific topics being discussed, other cabinet members, agency heads, or subject matter experts may be invited to participate.

The rhythm of this process can be intense, with daily intelligence briefings for senior policymakers, regular contributions to IPCs and DCs, and rapid turnaround times for urgent requests. IC professionals have to be adept at prioritizing tasks, distilling complex information into clear and concise points, and adapting their products to the needs of different levels of the policy process.

Relationship between the IC and policymakers

The relationship between intelligence and policy is not one-way. Policymakers also influence the intelligence process by setting priorities, requesting specific information, and providing feedback on intelligence products. This ongoing dialogue helps ensure that intelligence remains relevant and responsive to policymakers’ needs while maintaining its independence and objectivity. So, intelligence products can be either tasked by policymakers or self-initiated by IC agencies.

- Tasked production: Responds directly to policymaker requests, ensuring relevance to current decision-making needs. This could involve answering specific questions about a foreign leader’s intentions, assessing the capabilities of an adversary’s weapons system, or analyzing the potential outcomes of a proposed policy action.

- Self-initiated production: Allows agencies (and individual analysts) to proactively identify and analyze emerging threats or opportunities that policymakers might not yet be aware of within existing policy and intelligence priorities. This could include identifying early warning signs of political instability in a region, detecting nascent technological developments with national security implications, or uncovering previously unknown foreign intelligence operations.

Balancing these two types of production shapes the day-to-day for analysts working their “accounts,” particularly those with higher-tempo accounts (e.g. active conflict zones with core US interests and assets) or those working longer, more strategic accounts that have less production driven by policymaker reactions. Typically, analysts will do a mix of both tasked production and self-initiated production on policy-relevant issues within an office’s “program of analysis,” or research agenda.

Policy preferences and intelligence estimates: a complex relationship

Throughout history, the line between objective intelligence and policy preferences has often blurred, creating a complex and sometimes confrontational dance between analysts and policymakers. This intricate interplay, fraught with potential pitfalls, has been a persistent challenge throughout the history of intelligence work.

- Iraq War (2003): The Bush administration’s desire to intervene in Iraq may have led to an overemphasis on intelligence supporting the existence of WMD. The infamous “Curveball” source provided flawed intelligence that aligned with policy preferences, leading to faulty assessments.

- Team B Exercise (1976): During the Cold War, a group of outside experts (Team B) was allowed to analyze classified intelligence on Soviet military capabilities. Their assessment, which was much more hawkish than CIA’s, was arguably influenced by their pre-existing policy preferences for a more confrontational approach to the USSR.

- Vietnam War (1960s-1970s): Some intelligence historians argue that military intelligence components, particularly in the US Army, consistently provided overly optimistic assessments of the war’s progress. This may have been influenced by a desire to support the military’s preferred strategies and to maintain public support for the conflict.

- Bay of Pigs Invasion (1961): CIA’s estimates of popular support for an uprising against Fidel Castro in Cuba were influenced by the Kennedy administration’s strong desire to overthrow the Castro regime. This led to overly optimistic intelligence assessments that contributed to the operation’s failure.

IC analysts must navigate a minefield of cognitive biases, institutional pressures, and the ever-present specter of politicization, all while striving to deliver clear, accurate, and timely assessments to decision-makers who hold the reins of national power. This ongoing struggle to maintain analytical rigor in the face of policy currents underscores one of the most fascinating and critical aspects of intelligence work.

Intelligence work on emerging technology topics

Intelligence and emerging technology work are closely linked along the entire intelligence process, from focus of collection and analysis to developing new capabilities for use by operational entities. The IC’s involvement in emerging technology can include:

- Analyzing adversaries’ technological capabilities and intentions

- Assessing foreign nations’ research and development (R&D) progress in areas like AI, quantum computing, biotechnology, and hypersonic weapons.

- Identifying potential military applications of emerging technologies by adversaries, and evaluating their impact on military doctrines and strategies.

- Monitoring technology transfer and acquisition efforts by foreign entities.

- Developing internal capabilities to leverage new technologies

- Implementing AI and machine learning for data analysis and pattern recognition to enhance intelligence gathering and processing.

- Exploring quantum computing applications for cryptography and data analysis.

- Utilizing advanced data analytics and big data technologies to process vast amounts of information.

- Developing cutting-edge cybersecurity tools to protect sensitive information and systems.

- Creating innovative collection methods using emerging technologies.

- Assisting policymakers in understanding global risks and opportunities associated with emerging technology

- Assessing how emerging technologies might alter global power dynamics.

- Identifying potential disruptive impacts across economic, military, and social sectors.

- Alerting to early signs of significant technological breakthroughs.

- Offering insights on ethical and societal implications of new technologies.

- Forecasting long-term technological trends and potential “black swan” events.

- Supporting technology governance and policy formulation

- Informing international negotiations on technology governance, such as AI ethics guidelines or cybersecurity norms.

- Assisting in the monitoring of export controls and non-proliferation controls, particularly as it relates to malign state and non-state actor groups.

- Providing intelligence to support decision-making on research funding priorities.

- Collaborating with the private sector and academia

- Engaging with tech companies and research institutions to stay abreast of technological advancements.

- Facilitating public-private partnerships to address national security challenges related to emerging technologies.

- Supporting academic outreach programs to nurture talent in critical technology areas.

- Countering foreign technology-based threats

- Identifying and mitigating foreign attempts to steal sensitive technological information.

- Assessing and countering disinformation campaigns enabled by advanced technologies.

- Analyzing potential vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure due to emerging technologies.

- Supporting arms control and non-proliferation efforts

- Providing technical expertise for verification of arms control agreements involving emerging technologies.

- Monitoring the development and spread of dual-use technologies that could contribute to WMD programs.

- Investing in and conducting advanced technological research and development

- Conducting internal R&D programs to develop bespoke technologies for intelligence collection and analysis.

- Funding high-risk, high-payoff research in the private sector through the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), aimed at addressing unique intelligence challenges and requirements.

- Supporting strategic investments in innovative technologies from start-ups through In-Q-Tel, CIA’s venture capital arm, to enhance intelligence capabilities.

The IC’s work in emerging technology policy requires professionals who can combine deep technical knowledge with an understanding of geopolitics, strategic analysis, policy processes, and how national security decision-making works. Importantly, they must be able to communicate complex technical concepts to non-technical policymakers and translate policy needs into actionable intelligence requirements. Moreover, the rapid pace of technological change means that intelligence professionals in this field must continuously expand their knowledge and skills. Many IC agencies offer specialized training programs and encourage participation in academic conferences and industry events to stay current with the latest developments.

IC components relevant to emerging technology

The IC is deeply involved in work related to emerging technologies, both in leveraging these technologies for intelligence work and analyzing their impact on national security. Key areas of focus include:

- AI and machine learning: For example, NSA’s AI Security Center explores the security implications of AI, CIA’s Directorate of Digital Innovation investigates AI applications for data analysis, and NGA is harnessing AI for geospatial intelligence analysis. Key focuses include:

- Analyzing adversaries’ AI capabilities and intentions

- Developing AI tools for intelligence analysis

- Assessing the impact of AI on global strategic stability

- Supercomputing and quantum computing research: Recognized by ODNI as critical emerging technologies, quantum computing and supercomputing are focus areas for several IC agencies. NSA, for instance, is researching quantum-resistant cryptography to prepare for the potential threat to current encryption methods. The national labs, which aren’t technically part of the IC but regularly work with IC agencies on issues requiring extensive technical expertise, also work in coordination with DOE to conduct national security-related supercomputing work. Key focuses include:

- Monitoring global progress in quantum technologies

- Assessing threats to current encryption methods

- Exploring quantum sensing’s impact on stealth technologies

- Biotechnology: DIA’s National Center for Medical Intelligence monitors global health threats and biotech developments, while ODNI’s National Counterproliferation and Biosecurity Center has programs focusing on biotech advancements and their potential security implications. Key focuses include:

- Detecting potential development of engineered pathogens by state or non-state actors

- Analyzing synthetic biology’s impact on global security

- Space technology: NRO leads in developing, procuring, and operationally managing intelligence satellites, while Space Force Intelligence focuses on threats to space-based assets and adversary space capabilities, reflecting the growing importance of space in national security. Key focuses include:

- Assessing threats to critical satellite infrastructure

- Analyzing the impact of commercial space activities on intelligence gathering

- Cybersecurity: NSA’s Cybersecurity Directorate spearheads efforts to secure national security systems, while DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), which isn’t part of the IC but also regularly engages with the IC on issues involving cyber threats affecting domestic industries, works on protecting critical infrastructure in the face of evolving cyber threats. Key focuses include:

- Defending against and conducting cyber intelligence activities

- Analyzing emerging cyber threats and vulnerabilities (e.g. with advances in AI or the development of 6G networks)

IC work on AI issues

The IC is becoming increasingly involved in AI efforts, primarily through coordination with other government entities like DOD’s Chief Digital and AI Officer (CDAO), as well as DOC and DOE AI-related initiatives. For example, NSA’s AI Security Center focuses on AI’s security implications in offensive and defensive contexts, and on monitoring adversary capabilities in this space.

Intelligence work itself is evolving in response to new AI technologies and various reports are considering AI’s applications for intelligence work. Analytical work increasingly involves machine learning for data processing and pattern recognition, and AI is being explored for automating certain aspects of intelligence collection and processing. This increasing integration into intelligence work has also created a demand for more technical AI and machine learning skills—for example, data scientists and machine learning engineers are needed to develop and implement AI models for various applications in intelligence analysis, while specialized skills in AI security and evaluations could be useful to assess vulnerabilities in AI systems and develop countermeasures. The application of AI into intelligence work is also shaping INT-specific disciplines; OSINT officers, for example, can use AI tools to collect and analyze open-source intelligence. Finally, the IC’s enforcement and monitoring capabilities will be critical for any future international AI governance agreements.

IC work on biosecurity and countering WMD

Parallel to AI efforts, the IC plays a crucial role in addressing major risks stemming from biological threats and weapons of mass destruction (WMD), including efforts to detect and prevent the spread of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. Key organizations in this space include DIA’s National Center for Medical Intelligence (NCMI), which monitors global health threats and biotech developments, ODNI’s National Counterproliferation and Biosecurity Center (NCBC), which coordinates efforts to detect and prevent WMD threats, and DHS’s Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction Office (CWMD). The National Intelligence Council (NIC) collaborates with academia and industry to better understand and anticipate technological developments that could impact national security.

Roles in biosecurity and WMD counterproliferation (CP) are equally diverse. Biosecurity analysts, for example, assess global biological threats and monitor advancements in biotechnology. This track could be a good fit for applicants with a background in biology and an understanding of global health systems, but there are also opportunities to cross-train in the IC without a technical background. In other domains, WMD specialists monitor and analyze the development and proliferation of nuclear, biological, and chemical, necessitating knowledge of weapons systems and international relations. More technical specialists, like bioinformatics experts apply data science and AI to biological data for threat assessment and prediction, while CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear) analysts assess threats and develop countermeasures in these specific areas.

IARPA and In-Q-Tel

Two unique IC organizations play pivotal roles in driving technological advancement and ensuring access to cutting-edge capabilities: the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) and In-Q-Tel. While both organizations aim to bolster the IC’s technological capabilities, they approach this goal differently. IARPA focuses on high-risk, high-reward research projects that push the boundaries of science and technology, while In-Q-Tel operates as a strategic investor, bridging the gap between the IC’s needs and emerging commercial innovations.

Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA)

IARPA, established in 2006, is the IC’s version of DARPA (DOD’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency). It operates under ODNI as an independent entity and focuses on “high-risk, high-payoff research programs to tackle some of the most difficult challenges facing the intelligence community.” IARPA doesn’t have its own laboratories but instead funds research through academia, industry, and national laboratories. IARPA’s research portfolios are managed by “Program Managers”, who are experts usually from other IC or government entities hired for five-year fixed terms. IARPA’s research programs span many areas including machine learning, quantum computing, biometrics, neuroscience, and advanced computing.

In-Q-Tel

In-Q-Tel, founded in 1999, is a strategic investor that accelerates the development and delivery of cutting-edge technologies to US government agencies, primarily CIA. Operating as a not-for-profit venture capital firm backed by the US government, In-Q-Tel’s mission is to bridge the gap between the IC’s technology needs and emerging commercial innovation in private industry, primarily small-scale companies and ventures. It invests in startup companies developing technologies that have both commercial potential and relevance to intelligence and national security missions. Areas of focus include AI, data analytics, biotechnology, autonomous systems, and cybersecurity. While some opportunities for temporary assignments to In-Q-Tel exist, many of its staff are employed separately from the IC.

Working in the IC

Securing an IC job requires careful preparation and patience. Here are some key steps and considerations:

- Research: IC agencies vary widely in their topic focus and available roles, so thoroughly investigate different IC opportunities to find the best fit for your skills and interests.

- Education: Most IC positions require at least a bachelor’s degree. While many applicants also have master’s degrees, extensive work experience can sometimes compensate for lack of an advanced degree. PhDs can also be advantageous for highly specialized roles or research-intensive positions, particularly in STEM fields, while JDs are required for legal roles (e.g. in each agency’s Office of General Counsel). For IC roles, almost any major or field of concentration can be relevant:

- Political Science, Public Policy, International Relations, and Security Studies degrees are popular and highly relevant for many IC roles, especially for analyst positions. Some master’s programs, like the Security Studies Program at Georgetown University, offer intelligence concentrations specifically tailored for IC careers.

- STEM degrees are highly valued for technical roles in cyber operations, data science, cryptography, and other weapons and technology analysis. Computer Science, Data Science, and Engineering degrees are especially in demand. Economics degrees are also valuable for roles analyzing economic intelligence or financial crimes.

- Language and Area Studies degrees can be crucial for roles focusing on specific regions or cultures.

- Experience: Internships, co-op programs, or entry-level positions can provide valuable experience, including for undergraduates and recent graduates. One advantage of many IC internships is that they can be an especially fast way to get a security clearance early in your career. Types of experiences particularly helpful for IC jobs include:

- Previous government or military service, especially in roles requiring security clearances (e.g. Top Secret/SCI).

- Internships or work experience in think tanks, particularly those focused on national security or foreign policy.

- Research assistantships in relevant academic fields.

- Private sector experience in consulting, political risk analysis, cybersecurity, data analysis, or emerging technologies development.

- International experience, including study abroad, Peace Corps, or work with international organizations.

- Volunteer or work experience with crisis management or emergency response organizations.

- College activities like participation in model UN, war gaming exercises, or similar simulations.

- Technical projects or hackathons demonstrating skills in coding, data analysis, or cybersecurity.

- Any degree of writing experience, particularly analysis of current events or technical topics for a general audience, or time spent abroad.

- Security clearance: Be prepared for a thorough background investigation. Start early, as the process can take 6-12 months or longer.

- Networking: Attend career fairs, information sessions, and leverage alumni networks to learn more about IC opportunities.

- Stay informed: To strengthen your candidacy and prepare for future IC roles, keep up with current events, geopolitical issues, and technological developments relevant to national security.

- Patience: The hiring process can be lengthy. Stay persistent and consider other opportunities (e.g. think tanks, Congress, and other federal agencies) while waiting.

Desired qualities and skills

Some general characteristics critical for many IC roles include:

- Must be a US citizen

- Strong analytical and critical thinking skills

- Ability to work in classified environments and maintain confidentiality

- Interest in national security and international affairs

- Adaptability and willingness to learn continuously

- Strong communication skills, both written and verbal

- Proficiency in critical languages (e.g. Mandarin, Arabic, Russian) can be a significant advantage, especially for regional analysts.

- For tech-focused roles, build your technical skills, credentials, and work experience. Aim to stay current with relevant technologies and consider obtaining industry certifications (e.g. in programing, cyber security, machine learning).

Briefing skills for IC work

One of the most crucial skills for intelligence professionals is the ability to deliver effective briefings. Whether you’re an analyst, collector, or technical officer, you’ll likely find yourself presenting complex information to policymakers, military leaders, or other intelligence professionals. Key aspects of intelligence briefings include:

- “Bottom Line Up Front” (BLUF): Learn to lead with your main points or conclusions, then provide supporting details. This is crucial because most of the time, you’ll likely be briefing senior officials with limited time—turning what was supposed to have been a 20 minute deep-dive into a 2 minute “wavetops” briefing.

- Clarity and concision: Analysts learn to quickly distill vast amounts of information into clear, concise points that busy decision-makers can quickly grasp and act upon.

- Adaptability: Briefings may range from formal presentations to the President or National Security Council, to impromptu updates for mid-level officials. IC officers have to tailor their approach to the audience and the situation.

- Visual aids: Analysts lean on in-house graphic designers to create and use effective visual aids, from traditional slides to more advanced data visualizations, to enhance understanding of complex issues.

- Answering questions: Be prepared to field difficult questions on the spot. This requires deep knowledge of the subject matter and the ability to think on your feet.

- Confidence and credibility: Project confidence while maintaining objectivity. Your demeanor can be as important as your content in establishing credibility.

- Security awareness: Analysts have to always be mindful of classification levels and who is cleared to hear what information.

Developing these briefing skills is an ongoing process throughout your intelligence career. Many agencies offer training programs to help refine these abilities, recognizing their importance in effectively communicating intelligence to decision-makers.

Job and internship listings

Our IC components chart includes links to the hiring websites of all 18 IC agencies. Most offices also post internships and publicly available positions to USAJOBS.gov.

Since many IC components are part of the DOD, some entry-level DOD internships and fellowships can also serve as IC entries (e.g. Boren Awards, SMART Scholarship, McCain Strategic Defense Fellowship).

The Virtual Student Federal Service (VSFS) program is a part-time, remote, unpaid internship program that hosts interns across US government positions, including multiple components of the IC. Since VSFS internships don’t require a security clearance, application overhead is lower, but the scope of IC listings is also more limited.

In addition to the Federal Internships Portal on USAJOBS.gov, many IC agencies include internship and early-career program information on their websites. Because many of these programs require security clearances, the application process often begins over a year before the start of the program. Here are some examples of relevant IC internship programs (not exhaustive):

List of IC internships and other early-career programs

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA): offers a paid, year-round internship and co-op program and a scholarship program for undergraduate and graduate students. Interns work alongside full-time intelligence analysts to assess unclassified and classified information for customers such as the President, National Security Council, and other US policymakers. A minimum of one 90-day tour is required for the programs, which are in-person in Washington DC and require applicants to go through the full security clearance process. The financial needs-based Stokes Scholarship program offers recipients up to $25,000 in tuition assistance in addition to the year-round salary. All scholarship recipients must work at CIA for a period of 1.5 years per post-graduation year of paid scholarship received.

- Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI): ODNI runs a new talent exchange program, the Intelligence Community Public-Private Talent Exchange (IC PPTE). This program enables temporary exchanges between the IC and companies in certain technology sectors, with a focus on AI, data management, economic security, human capital, and space technologies.

- National Security Agency (NSA): offers summer internships, high school work-study programs, and co-op programs. Opportunities are located at NSA headquarters in Fort Meade, Maryland, or at one of NSA’s field offices across the country.

- Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA): offers summer and academic semester internships and co-op programs. DIA also participates in the Stokes Scholarship program, and its Office of General Counsel offers an unpaid internship for law students for academic credit. Internships are posted to DIA’s job board.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI): offers a paid Honors Internship program for undergraduates, graduates, and PhD students at their main headquarters in DC or at one of their field offices. FBI also has a collegiate hiring initiative and entry-level openings for recent graduates, and a Visiting Scientist Program for early-career scientists to participate in forensic science research at the FBI Laboratory.

- National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA): offers paid summer internships for high school and college students in various office locations across the country.

- National Reconnaissance Office (NRO): offers a paid Cadre summer internship program for undergraduate and graduate students to support NRO’s national space mission. The internship allows students to transition to the NRO Developmental Career Path Program upon graduation. NRO also offers a military service and ROTC summer internship program for US Service Academy cadets and midshipman and ROTC students pursuing technical degrees related to the NRO’s mission.

- Department of the Treasury – Office of Intelligence and Analysis (OIA): The Treasury offers summer and academic semester internships for students. Students can select their preferred offices within the Treasury; OIA is part of the Treasury’s Terrorism and Financial Intelligence office. The Treasury also participates in the Pathways Programs for current students and recent graduates.

- Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI): ONI offers paid summer and academic semester internships at its Maryland office.

- Department of Homeland Security – Office of Intelligence and Analysis: offers paid internships for undergraduate and graduate students in DC, including in intelligence analysis, intelligence operations, mission readiness, and IT and data science.

Additional opportunities may be available for undergraduates at the US Naval Academy, US Coast Guard Academy, US Air Force Academy, ROTC programs, or the US Merchant Marine Academy.

Appendix: The different kinds of intelligence work

The “intelligence cycle”

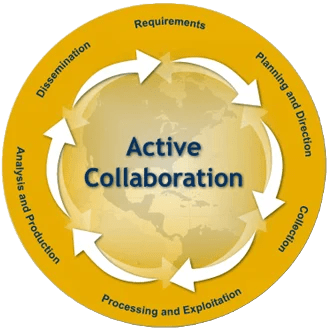

The intelligence cycle refers to the process by which intelligence agencies collect raw information, process and analyze that information to make sense of it, and disseminate it to policymakers to secure decision advantage. This process is typically broken down into constituent parts of the “cycle” that roughly correspond to various entities and jobs within the IC:

The intelligence cycle

- Requirements: The cycle begins with identifying the needs of intelligence consumers (policymakers, military commanders, etc.), known as intelligence or collection requirements. These requirements guide the entire intelligence process from collection to feedback.

- Planning and direction: Based on the requirements, intelligence leaders plan and direct the collection activities. This involves determining which collection disciplines are best suited for gathering the needed information.

- Collection: Raw information is gathered using various collection methods and sources. This can involve human intelligence, signals intelligence, open-source intelligence, and other collection disciplines.

- Processing: The collected raw data is converted into a form usable by analysts. This may involve language translation, decryption, and organizing data into databases.

- Analysis and production: Analysts evaluate and integrate data from multiple sources, interpret its significance, and produce finished intelligence products. These can range from brief current intelligence reports to lengthy estimative analyses.

- Dissemination: The finished intelligence products are distributed to the intended consumers. This can occur through written reports, oral briefings, or other means. The National Security Act of 1947 defines the IC’s primary customers as:

- The President

- National Security Council

- Heads of Departments and Agencies of the Executive Branch

- Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and senior military commanders

- Congress

- Feedback to both collectors and analysts is a continuous process that occurs throughout all parts of the intelligence cycle.

Types of intelligence (the “INTs”)

The IC is focused and structured by the various intelligence disciplines, often referred to as the “INTs”, also mentioned earlier:

Types of intelligence: from HUMINT to CYBINT

- Human Intelligence (HUMINT): This involves information gathered from human sources. It can include overt collection by known government officials and clandestine collection by operatives who recruit and “run” human sources, known as “agents” or “assets,” inside entities of focus.

- Signals Intelligence (SIGINT): This involves intercepting and analyzing electronic signals and communications. It includes communications intelligence (COMINT), electronic intelligence (ELINT), and foreign instrumentation signals intelligence (FISINT).

- Geospatial Intelligence (GEOINT): This includes imagery intelligence (IMINT) and geospatial information. It involves analyzing images of the Earth’s surface and features to describe, assess, and visually depict physical features and human activities.

- Measurement and Signature Intelligence (MASINT): This is technically derived intelligence that detects, tracks, details, or identifies specific characteristics of fixed and dynamic target sources like adversary military systems. It can include chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear intelligence.

- Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT): This involves collecting and analyzing publicly available information from various sources such as social media, public data, and academic publications.

- Financial Intelligence (FININT): This involves gathering information about the financial affairs of entities of interest to understand their nature and capabilities, and to determine the sources and vulnerabilities of funding streams for national security-relevant activities.

- Cyber Intelligence (CYBINT): This involves collecting and analyzing information from cyber systems and networks to inform decision-making.

Each of these intelligence types has its strengths and limitations, and analysts often use them in combination to provide a comprehensive intelligence picture, a process known as “all-source analysis.” While some IC analysts specialize in a particular intelligence discipline (e.g. GEOINT analysts at NGA or SIGINT analysts or linguists at NSA), many IC analysts are trained in all-source analysis, integrating information from multiple intelligence types to produce comprehensive assessments. CIA, as the nation’s premier all-source intelligence agency, is the primary organization for conducting and disseminating all-source analysis to policymakers.

Testimonials

“My CIA career has been incredibly rewarding and diverse. I started as an intern and progressed through roles in political and targeting analysis, focusing on the Near East, counterintelligence, and emerging technologies. I’ve worked overseas, served as an Executive Assistant to an Assistant Director, and led integrated operational and analytic teams. These experiences have given me unique insights into field operations, policymaking support, and the crucial interplay between analysis and operations.

The work has been meaningful and impactful—from countering national security threats to briefing senior policymakers. I’ve had opportunities to learn advanced technologies, dive into complex analytics, and even pick up a new language. Navigating a large bureaucracy can be challenging, and you need resilience for moments of frustration, but being proactive and working with inspiring colleagues has been key.

The variety of experiences—from field operations to headquarters analysis to executive-level support—and the tangible impact of the work make this career uniquely fulfilling. My journey through different roles has given me a comprehensive view of the Agency’s crucial work in safeguarding national security. It’s been challenging at times, but incredibly rewarding.”

Additional resources

- Intelligence Careers: A joint IC recruitment portal

- ODNI’s Guide to the Intelligence Community

- “How to Be a Good Intelligence Analyst”: Episode of the Statecraft podcast featuring an IC expert

Related articles

If you’re interested in pursuing a career in emerging technology policy, complete this form, and we may be able to match you with opportunities suited to your background and interests.